Nature has tried some pretty wild approaches to life’s problems over the centuries, and that includes vision.

One of the earliest examples of a complex eye may have been based on a rather unusual material to focus light, one not found in modern organisms. The eyes belonged to an extinct group of animals called trilobitesand their eyes were made of hard crystal, a mineral known as calcite — a strange little quirk that gives us a glimpse into how these early animals sensed the world around them.

Trilobites became extinct about 250 million years ago, but existed for about 300 million years before that. There are also numerous trilobite body plans in the fossil record, suggesting that those 300 million years were very successful years. And because their strange eyes were made of stone, they were often well preserved in the many fossils they left behind.

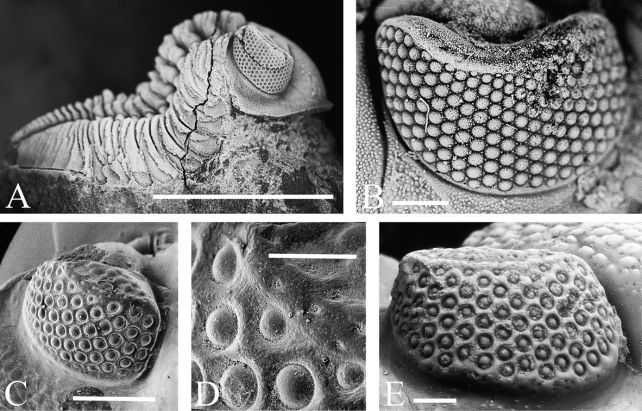

That’s how we know they had trilobites compound eyes like insects, made up of clusters of photoreceiving units called ommatidia, each with its own photoreceptors and lenses. Examining broken parts of the fossilized lenses reveal a crystalline material made of calcite.

Pure calcite is transparent, so in theory light could penetrate it and be focused where the photoreceptors could detect it. Similar to insect vision, there was probably a trade-off: Trilobites probably didn’t see in high spatial resolution, but they were extremely sensitive to motion.

There were three types of these trilobite eyes. The oldest and most common is a type known as holochralin which small ommatidia were covered by a single corneal membrane, with the adjacent lenses in direct contact with each other.

The abathochroal eye runs only in the family Eodiscidae; the tiny lenses are each covered by a thin cornea.

Finally, the schizochroic eye is only seen in the Phacopina suborder. The lenses are larger, spaced far apart, and each has its own cornea. They were likely, scientists believe, highly specialized.

The holochroal eye is most similar to modern eyes apposition seen in some insects and crustaceans, and scientists think they worked in a similar way. Each ommatidium works separately and the image the insect sees is one mosaic of all images combined.

However, things get a little tricky with calcite. Calcite has one of the strongest birefringences in nature. That means it has two refractive indices; will be light split twice as it travels through calcite, the two jets travel at different speeds, creating a double image.

For small ommatidia, as seen in the holochroal eye, this is probably no problem; the deviation in the rays is smaller than the photosensitive organ.

For the schizochroic eyes, birefringence is a bigger problem. Crystal is not flexible, so the larger ommatidia cannot change its focus to lessen its effect. Instead, scientists have discovered that schizochroic eyes have a so-called a double lens structure.

That means the lens has two layers, each with a different refractive index, that can correct for birefringence, much like the trilobites had built-in glasses. Lenses of this type were invented separately by mathematicians René Descartes and Christian Huygens in the 17th centuryunaware that trilobites had beaten them to the bone.

However, for all our understanding of the different structures of the trilobite’s eye, we still don’t fully understand how the schizochroic eye worked, whether it was similar to an apposition eye or did something different, since the different structure would recommend.

A recent study showed that schizochroal eyes are much more complex than we thought, which brings us closer. Each lens appeared to cover its own small compound eye, forming a kind of “hypereye”.

It could even be possible that we were completely wrong about seeing trilobites. A study questions from 2019 whether the calcitic corneas may have been artifacts of the preservation process, implying that their crystal eyes are much less unique than many speculate.

We still don’t know why this type of eye arose – if at all – or what benefits it brought, but now scientists are studying trilobite vision have a new way of looking at it.