Alzheimer’s drugs work by targeting amyloid plaques in the brain. Research studies of those drugs, known as clinical trials, take on a broader target: proof in the form of specific clinical endpoints for each study. Today’s Alzheimer’s trials endpoints are typically a piece of paper published in 1993 and originally developed in the early 80’s.

The Clinical Dementia Rating, or CDR, “is a 5-point scale used to characterize six domains of cognitive and functional performance applicable to Alzheimer disease and related dementias: Memory, Orientation, Judgment & Problem Solving, Community Affairs, Home & Hobbies, and Personal Care.”

Ratings are based on a clinician’s “semi-structured interview of the patient and a reliable informant or collateral source (e.g. family member).” Here’s the scoring table, whose rules start with this helpful suggestion: “Use all information available and make the best judgment.”

So much for precision neuroscience.

Based on dementia’s symptoms, psychological impact on caregivers and family, and the nature of the assessment itself, this tool is subjective at a human level, unreliable at a scientific level, and outdated at a common sense level.

That such retrograde tools remain a gold standard in dementia research around the globe may strike non-scientists as odd, or worse. Since the mid-1990’s, Pharma has spent $42.5 billion on Alzheimer’s trials; conservative cost estimates of Eisai and Lilly’s recent trials are $3 billion apiece. The former used CDR as a primary endpoint for Lequembi (approved in May 2023) and the latter as a secondary endpoint for donanemab (FDA approval pending.)

Yes, there were several other endpoints in both trials, including other (similar) rating scales along with various imaging tools like MRI and CT scans to measure side effects like brain swelling and pre/post comparisons. Yes, these methods have worked in the past. But we’re not pre-Y2K anymore: Neurotech and digital tools are showing they can measure a gamut of brain function and cognitive health in clinical settings.

Meanwhile, millions of patients, family members, and caregivers are floundering under the weight of a disease that continues to rob people of their humanity, while costing an estimated $345 billion per year and growing.

Everyone wants a cure. So why is research still stuck in the 20th century?

Calls for more evidence: A DiME a dozen

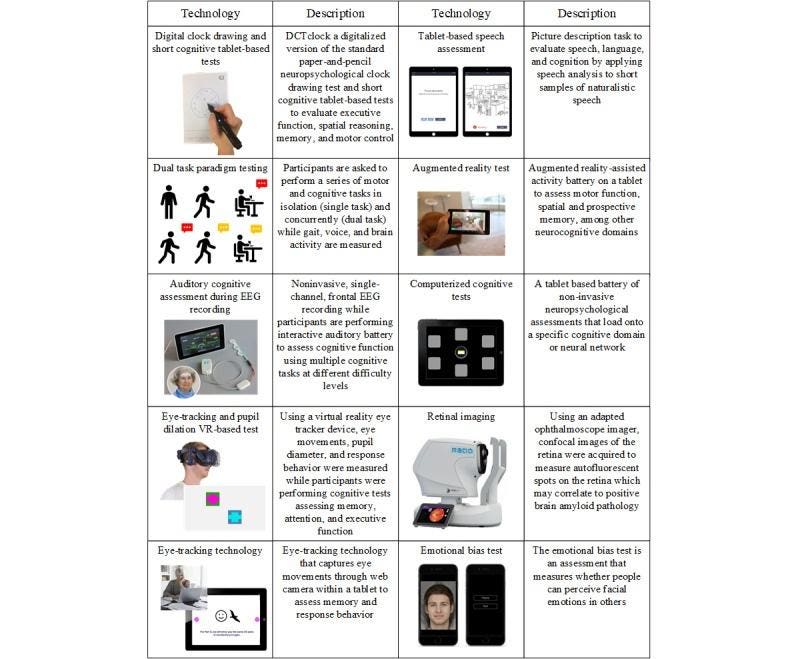

“More accurate and reliable efficacy endpoints could potentially reduce the number of failed or inconclusive trials and allow for more efficient drug development through shorter, smaller, less costly, and less burdensome drug trials, ultimately allowing more drugs to be studied and medicines to reach patients faster,” explain a squad of industry-embedded authors of a 2022 paper that cataloged ten digital approaches to measuring cognitive health.

MEDIA: Method for Evaluating Digital Endpoints in Alzheimer Disease looked at 10 novel tools for use … [+]

“However,” they continue, “it remains unclear how to best evaluate a wide range of novel and promising technologies, how to use them to derive efficacy endpoints, and how to advance them through early drug development processes.”

Nobody says we should use unproven tools in clinical research. But how much evidence is enough? An aptly titled paper published last summer by Dr. Brian Perry of the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative asks the very question, while pointing to reams of published digital measures, recommendations, best practices, playbooks, and other resources.

A group called the Digital Medicine Society (DiME), founded four years ago to close this evidence gap, has published “172 pieces of evidence and growing” in Alzheimer’s and dementia alone. The library is a tremendous resource, insightful both for the diversity and creativity of measures coming down the pike, as well as the mounting evidence that the paper age is overstaying its welcome.

New Players for a New Era

“Many of the validated cognitive assessments today are paper based, introducing the potential for bias and limiting ethnic and geographic diversity in clinical studies,” according to Dr. CJ Barnum, neuroimmunologist and VP of Central Nervous Disorder (CNS) Development at Inmune Bio. He spoke on a recent webinar sponsored by Cumulus Neuroscience, a neurotech startup leveraging electroencephalography (EEG) and other data to improve clinical trials.

Dr. Barnum called for smaller, faster, more specific clinical trials, arguing that small biotech companies leveraging novel neurotechnologies will be the ones to lead this charge. One example of the future comes from Kernel, a startup whose study of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), a possible precursor to Alzheimer’s disease, uses primary endpoints derived entirely from wearable neurotechnology that measures blood flow in the brain using infrared light.

Chris Benko, founder and CEO of Koneksa, has been working on digital biomarkers for the last decade, including several areas of neurology. “We believe data from digital health technologies has every bit as much potential to change how we develop medicine as pharmacogenomics has, for instance,” he told me. “But, it doesn’t get to skip steps just because it’s technology.”

Benko, who spent 20 years at Merck before spinning out Koneksa, walked me through a smartphone tremor assessment for Parkinson’s disease, underscoring the long path to both technical and clinical validation, the challenge and opportunity in transforming how pharma leaders make decisions, and the expertise required to know when to digitize certain legacy rating scales, versus leapfrogging them.

When I asked about neurotech’s specific potential in this vein, he pointed me to their collaboration with Beacon Biosignals to discover and validate measures using “at-home EEG, wearables, and smartphones.”

Another startup leading this charge is Altoida, whose cognitive health test has been extensively studied, including in both the paper and DiME’s library of published measures linked above.

When I asked CEO Marc Jones about how much evidence will be enough to make tools like Altoida’s mainstream in Alzheimer’s trials, he drily quoted JD Rockefeller: “Just a little bit more.”

Altoida’s 10-minute, interactive augmented reality (AR) test for dementia is not necessarily designed to displace paper measures, but rather to enable earlier detection and treatment to restore healthy aging in dementia patients. “We’re not just looking at if someone is impaired or not, we’re using AI to figure out where.”

Altoida’s test is undergoing a pivotal trial before the FDA can award it clearance as an “official” diagnostic test for use by doctors, following its Breakthrough Device status in 2021. Becoming a cleared diagnostic test may help drive broader adoption as a clinical trial endpoint, but it will ultimately be up to pharmaceutical sponsors.

That being said, Jones pointed to numerous head-to-head comparisons with standard measurement tools, six peer reviewed publications, the most recent in Nature. Besides ongoing collaboration with DiME, they’ve also built strategic partnerships with industry leaders like Eisai.

It’s important to note that the progress of the above companies still represent the exception rather than the norm when it comes to new measurements in Alzheimer’s trials. As Dr. Perry’s paper points out, “Some sponsors noted that without specific guidance from regulators, it was unclear how much evidence was needed for regulatory approval, and this made it difficult to plan the trial’s endpoints.”

Gravity of the Situation

Anyone who works in healthcare knows that grumbling about the FDA is easy. But pulling Alzheimer’s research into the 21st century will not be, even with a cooperative and willing agency – which by most indications, the FDA is becoming. Measurement is practically the whole game in clinical trials, and patient safety is paramount. Setting a new gold standard in human research will require ongoing and endless scientific and technical excellence from all new entrants, as well as concerted leadership from all corners of industry and government.

One signal of change is DiME’s latest collaboration, which seeks to bridge the gap between digital measures with ample clinical evidence, and shortcomings in industry uptake. The expanding focus from evidence generation to commercial adoption suggests that economics of pharmaceutical research is reaching a tipping point.

Life sciences executives are clamoring for more efficient trials, new real world evidence, and better, objective (and I’ll add, patient reported) measures of cognitive decline, drug efficacy, and health. I see this as writing on the wall that 2024 will be a bumper year for neurotech startups selling into the life sciences companies.

Undeniably, progress towards a 21st century research process for Alzheimer’s treatments is inching forward, one global collaborative here, one funding round for non-drug treatment there. But what if the right team— led by someone extremely rich, powerful, tech-savvy, and visionary in global health — just decided, explicitly and unambiguously, that after three decades, paper measures need to become yesterday’s news?

Startup Health’s newly announced Alzheimer’s Moonshot is backed by the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Fund’s dedicated Diagnostics Accelerator (DxA), as well as the private office of Bill Gates himself: “DxA (is) a $100 million global research initiative dedicated to fast-tracking the development of biomarkers and diagnostic tools. The DxA aims to develop these tools to aid with the early detection and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s.”

New diagnostics could – and many believe will – change how clinical research is done in Alzheimer’s, neurological disorders, and beyond.

Here’s hoping Mr. Gates et al will do better than moonshots with paper planes.